Our Habitat Haven volunteers have begun site visits and been enthusiastically received. At the start…

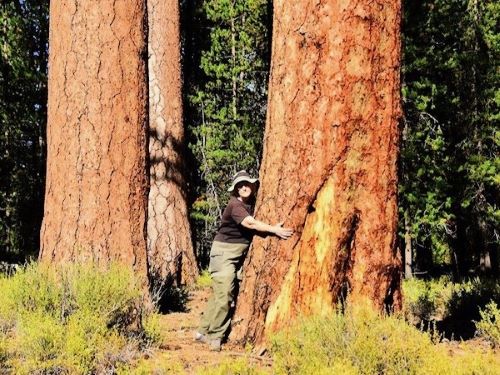

The O&C lands consist of 2.8 million acres of public land in western Oregon. Originally given to the Oregon & California (O&C) Railroad Company in 1866, they were put into the public trust under federal management in 1937. Even after years of timber harvesting, these lands represent some of the best mature and old growth forest in the western United States. Counties with O&C lands received money when the forests were logged, and they came to rely on these funds. In 2000, the struggling counties began receiving federal funds, which continued each year to give them time to develop better economic models. Unfortunately, they did not do so, and the counties are now in crisis…

The O&C lands consist of 2.8 million acres of public land in western Oregon. Originally given to the Oregon & California (O&C) Railroad Company in 1866, they were put into the public trust under federal management in 1937. Even after years of timber harvesting, these lands represent some of the best mature and old growth forest in the western United States. Counties with O&C lands received money when the forests were logged, and they came to rely on these funds. In 2000, the struggling counties began receiving federal funds, which continued each year to give them time to develop better economic models. Unfortunately, they did not do so, and the counties are now in crisis.

Previous plans to clear cut large swaths of older forests were found to be illegal; despite this fact, the O&C Trust, Conservation, and Jobs Act (proposed legislation now before the US Congress) would divide the O&C lands into a logging trust and an environmental trust. Logging would be mandated and markedly increased on over 1 million acres of publicly owned forest, and it would be regulated under an older management plan that is currently in use only on private (but not public) lands. The long battle for a more scientifically sound management program, the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan, would be lost as regulations are rolled back. Implementation of the O&C Trust Act could be a dangerous step backwards for environmental stewardship in a state that prizes its forest legacy.

It seems a travesty to throw away the knowledge of forest management that has been accumulated over the years. Carefully managed logging could continue in a way that promotes commercial thinning in dense, younger forests and concentrates activity in replanted monoculture plantations—such a plan would not destroy our mature, diverse, resource-rich forests and the ecosystem services they provide. There has been little discussion on how the mandated timber harvest would be implemented while still adhering to federal laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act and others that protect water and endangered species. Some of the provisions of these laws would be ignored because the forests would be managed as private rather than public land.

Questions arise: Would land designated for logging undergo scientific scrutiny to ensure that the harvest complies with the law? What happens if surveys reveal that the timber take within the logging trust area is deemed unsuitable for logging under the law? Many people calculate that over 90% of Northwest forests are gone. The little that is left is being divided. What happens when this temporary fix—the O&C Trust Act—runs out and there are no trees left to log in the designated areas? Will the government then divide the land that was protected under the act and open it up for logging?

Oregon is rich in natural resources. Ramping up logging on this large scale will destroy habitat and pollute watersheds that provide water for Oregonians. About 75% of O&C lands are designated Drinking Water Protected Areas by the Department of Environmental Quality, and they provide water for close to 2 million people. Increased logging will add sediment to the water, destroy salmon runs, increase landslides, and remove our best source of carbon storage. The long-term economic costs of the extensive logging are not factored into the argument for the proposed legislation. For example, building and maintaining needed water treatment facilities, especially ones equipped to deal with increased sediment, could negate any economic benefit accrued from logging. The recreation and tourism industry would be severely affected as well. Recreational activities such as boating, hiking, fishing, and wildlife viewing contribute $12.8 billion to the state’s economy annually and support over 141,000 jobs, according to a recent study. Perhaps this industry, not logging, should be promoted through legislation.

The economic crises of the O&C counties need to be addressed with long-term solutions that are truly sustainable. Modern logging and milling techniques that use large automated machinery do not require many workers, and the work is often piecemeal and seasonal. People living in cash-strapped counties need an investment in training in diverse and sound jobs, in industries with growth potential, and in development that will not destroy the very resources we depend on.

What do the people of Oregon want? In a recent statewide poll commissioned by the Pew Research Center, a clear majority said that protection for land and water is their top priority. We recognize the long-term benefit that healthy forests provide, including clean air, clean water, and climate change mitigation. We value the birds and other wildlife that rely on this habitat. We wish to leave this legacy in good shape for our children and grandchildren.

For more information, go to http://oclands.org/.