Meet our new Habitat Haven volunteer. Evelyn Sherr has joined Lane Audubon’s Habitat Haven Backyard…

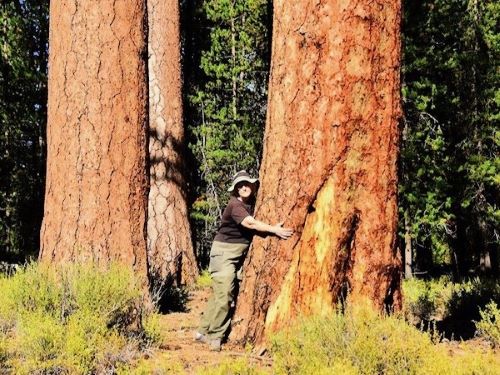

At one time, the Northern Spotted Owl was found in old-growth forests throughout the Pacific Northwest. Heavy logging and other developments over the last 190 years have reduced spotted owl habitat by 60%. As a result, owl numbers have declined by 40%–60% in the last 10 years, leaving an estimated 2,000 pairs in existence today.

At one time, the Northern Spotted Owl was found in old-growth forests throughout the Pacific Northwest. Heavy logging and other developments over the last 190 years have reduced spotted owl habitat by 60%. As a result, owl numbers have declined by 40%–60% in the last 10 years, leaving an estimated 2,000 pairs in existence today.

Because of this decline, the Northern Spotted Owl was declared a threatened species in 1990 by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). This status allows the USFWS to regulate activities on federal land that might harm the owl. In 1994, the Northwest Forest Plan became law; it provided protection for the spotted owl and as many as 600 other species that rely on old-growth forests. In the process, vital salmon runs were protected and clean water continued to flow from old growth.

Because many small and large logging companies and timber mills were outfitted for logging and milling large trees, they objected strongly to the new restrictions. They contended that they would have to curtail operations, leading to the loss of thousands of jobs. They predicted dire consequences from the resulting unemployment—“increased rates of domestic disputes, divorce, acts of violence, delinquency, vandalism, suicide, alcoholism and other problems.” Indeed, such social breakdown was possible, but that prospect didn’t stop the industry from rapidly increasing mill automation, mechanizing logging operations, and exporting raw logs, all of which led to greatly increased unemployment.

Had logging continued at the 1994 rate (125,000 acres per year), the old growth would have been gone within 30 years, thus simply postponing the mill closures.

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) not only requires protection for the listed species, it requires a recovery plan leading to high enough numbers so that the species can be taken off the list. The first recovery plan was issued in 2008 and, after thorough study, was revised in 2011; it indicates the need to continue protecting the spotted owl and the other species that rely on old-growth forests.

In response to pressure from the timber industry, the 2011 recovery plan allows continued “limited harvesting” in old-growth forests. In that plan, the USFWS recommends “protecting high quality and occupied spotted owl habitat and actively managing [logging] forests to restore their health.”

Forests are dynamic—they grow, change, and eventually die. The Northwest Forest Plan provides late-successional reserves (LSRs) in the spotted owl’s range. LSRs allow forests to continue to grow and to ultimately develop into old-growth forests.

It turns out that protecting old-growth forests is not enough to stop the decline of the spotted owl. A new threat to the owl has emerged since it was originally listed under the ESA. The Barred Owl has been expanding its range from the east and has reached the Pacific Northwest. This owl is larger and more aggressive than the spotted owl and has been displacing it. In a highly controversial plan, the USFWS is proposing an experimental program to shoot Barred Owls as a way to protect the Northern Spotted Owl.

See these websites for discussion of the proposed plan to shoot Barred Owls:

http://www.fws.gov/OregonFWO/Species/Data/NorthernSpottedOwl/BarredOwl

http://audubonportland.org/issues/species/bocomments-june2012

Learn More about the Northern Spotted Owl

http://www.fws.gov/oregonfwo/species/data/northernspottedowl/main.asp

http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v4n1/

http://kswild.org/what-we-do-2/biodiversity/species-profiles/nso

Update on the California Condor

A bill banning the use of lead from all hunting ammunition in California was signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown on October 11, 2013; nonlead ammunition will be phased in by 2019. The ban that was in effect only in condor habitat now extends to the entire state. Lead bullet fragments in carrion that condors eat has been responsible for many condor deaths.